by Rory Stott

This article was originally published in Arketipo Magazine issue 132 in October 2019.

Housing has been a central concern of architecture and theories about architecture for centuries. But there are two different types of housing architecture and historically speaking, the two types have not been considered equally. In two thousand years, there has scarcely been a period when one-of-a-kind houses, villas, and palaces for individual (and usually wealthy) families haven’t occupied a significant place in architectural discourse. But what of mass housing? Only during the Modernist era, when large multi-family housing blocks and extensive estates became an essential part of progressive “machine age” rhetoric, was collective housing for ordinary families considered as seriously as bespoke houses – despite the fact that collective housing is, by a dramatic margin, the bigger contributor of homes to global cities.

MVRDV is not opposed to single-family homes – indeed, we have even designed a number of them. But the office was founded on the back of a collective housing project, the Berlin Voids proposal that won the 1991 Europan competition and, ever since, collective housing projects have been a significant part of both our commercial work and our research. Our interest in them originates from two complementary impulses: firstly, like the Modernists, we believe in the moral obligation for architects to provide high-quality housing for as many people as possible; secondly, we are driven by the much newer moral obligation to create urban density, to use land and resources more efficiently, and thus to ameliorate the developing climate crisis.

Housing projects from the Modernist canon are therefore an important reference for us, but we also recognise Modernism’s significant flaws resulting from its sometimes black-and-white view of the world: it chose collectivism and homogeneity over individualism and diversity; the artificial over the natural; and top-down thinking over bottom-up. One of the central themes of MVRDV’s oeuvre is an attempt to collapse, through the use of spatial arrangement and architectural form, these various binaries – in other words, to develop housing typologies that update modernist ideals for a world that is not black-and-white, but complex and colourful.

The Collective vs The Individual

The patchwork façade of Silodam hints at the diversity of spaces inside. Image © Rob 't Hart

The patchwork façade of Silodam hints at the diversity of spaces inside. Image © Rob 't Hart

Modernism’s suppression of individuality in favour of collectivism is understandable, given its development alongside the emergence of socialism as a major political force, and the fact that modernism enabled the ambitious and progressive housing initiatives of socialist and communist governments alike. Considered in that light, the site for the 1991 Berlin Voids project – directly next to the former Berlin Wall in the then-recently reunited city – is symbolic, if only coincidentally. The project explicitly questions the Modernist pursuit of an ‘ideal’ home, and by extension its collectivist ideals, with the project text asking “does such a dwelling exist? Contemporary architectural thinking observes a shift from the pursuit of a singular housing solution to the need for variety and idiosyncrasy.” [1]

The project achieves this by developing a number of differently-shaped apartment types, which are arranged together like a puzzle. Each of these apartment types satisfies different user needs and desires, celebrating the individuality of the project’s occupants. Yet the project does not lose sight of collectivism, asking whether curiosity about neighbouring apartments might be the catalyst required to encourage residents to form community bonds.

.jpg) A prototype of the (W)ego concept displayed at the 2017 Dutch Design Week. Image © Ossip van Duivenbode

A prototype of the (W)ego concept displayed at the 2017 Dutch Design Week. Image © Ossip van Duivenbode

This apartment-puzzle strategy has since become a staple of MVRDV’s housing projects. It next appeared in 1997 with the Double House in Utrecht, in which two homes overlap and ‘intrude’ upon each other to accommodate the needs of two different neighbours on a constrained site. Another notable appearance came in the Silodam in 2003, where the patchwork nature of the façade hints at the complexity of the internal spaces within the simple rectilinear block. In this project a very active community has emerged over the years, right in line with the modernist ideal.

In recent years MVRDV has, along with The Why Factory (the think tank led by Winy Maas at TU Delft), worked on an important development to the apartment-puzzle typology known as (W)ego – a portmanteau of ‘we’ and ‘ego’ that perfectly encapsulates the drive to combine collective and individual impulses. The project envisages a hypothetical apartment building in which future tenants would engage in a type of game to try to carve out their perfect apartment while their neighbours simultaneously attempt to do the same. Software then mediates between the individual designs to create a collective slab.

Homogeneity vs Diversity

.jpg) The housing on Hagen Island combines standardisation and diversity. Image © Rob 't Hart

The housing on Hagen Island combines standardisation and diversity. Image © Rob 't Hart

Entangled with the binary opposition of individualism and collectivism is the binary opposition of homogeneity and diversity. Modernism embraced homogeneity as a logical extension of standardisation; Le Corbusier famously asserted that “all men have the same organism, the same functions” [2], and therefore later proposed “a single building for all nations and climates” [3]. Today, standardisation is a fundamental condition of the construction industry, but we also now understand how Le Corbusier’s evocation of the needs of “all men” excludes women, children, the elderly, and people with physical disabilities or neurological conditions – not to mention the range of lifestyles we need to answer to.

On Hagen Island, a part of the Ypenburg masterplan, MVRDV eschewed the simple solution of four long terraces of homes, instead cutting the four ‘bars’ into shorter sections and offsetting these sections from each other to create a garden-like environment where children play and neighbours encounter each other and interact in a variety of ways. The buildings themselves, meanwhile, are prefabricated, low-cost, and essentially homogenous, but their variety of materials, colours, positions, and sizes, gives them a sense of healthy diversity.

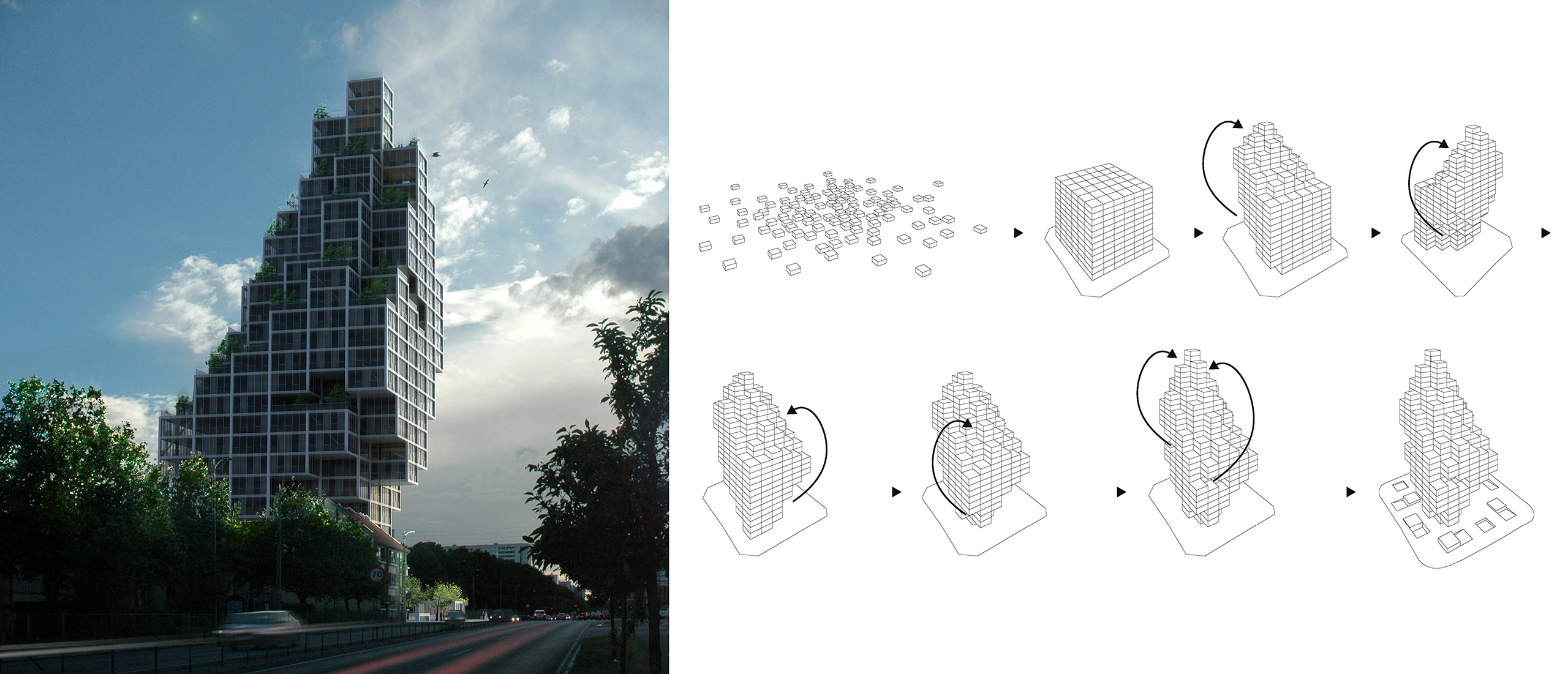

The pixel-based design of Rødovre Sky Village allows for flexible programming

The pixel-based design of Rødovre Sky Village allows for flexible programming

Another technique used to create diversity within the constraints of standardisation has been the ‘pixel’. One of MVRDV’s early implementations of the pixel as a design tool was in the proposal for Rødovre Sky Village, a project conceived in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis. With uncertainty surrounding the Danish real estate market, the pixelated tower was proposed as a solution that could easily be adapted to form either offices or apartments large or small – the 7.8-metre grid was highly flexible.

Since then, the flexibility of the pixel concept has been employed to enable diversity. Buildings can be constructed from an agglomeration of pixel units, and different programmatic elements can be accommodated by combining the space within multiple pixels. As Nathalie de Vries wrote in the recent manifesto for the “Architecture Speaks” exhibition in Innsbruck, the pixel is “the smallest [spatial] unit we work with – the one that can contain the ideal and construct the base”. [4]

Density vs Openness

.jpg) The hole in the Mirador building creates a public plaza on the 12th floor. Image © Rob 't Hart

The hole in the Mirador building creates a public plaza on the 12th floor. Image © Rob 't Hart

Density (and the potential of collective housing to create density) is of critical importance to MVRDV. But density often comes with downsides, as explained in Porocity, a publication of research conducted by Winy Maas with students at The Why Factory: “The production of density is usually connected with the idea of monumentality, solidity, and isolation… But we also want to preserve the well-being of small cities, places that are diverse, intense, and intimate.” [5]

MVRDV’s response to this concern has been to carve spaces within their buildings that perform the roles once given to public squares and community spaces. In the Mirador, completed in 2005 in Madrid, a large hole is punched through the building’s 12th–16th floors hosting a communal plaza space and a lookout framing the surrounding city.

Parkrand’s open spaces create terraces that extend the neighbouring park. Image © Rob 't Hart

Parkrand’s open spaces create terraces that extend the neighbouring park. Image © Rob 't Hart

In Parkrand, completed one year later in Amsterdam, an even more complex arrangement of housing blocks and voids is produced. The ground floor hosts communal patios on its roof between five tower blocks; above, these blocks are connected by a level of penthouse apartments. The communal patios, completed with a variety of furniture, lawns, playground equipment, and plants, are envisaged as a raised extension of the neighbouring park and an outdoor 'living room' for residents of the building.

Urban vs Rural

.jpg) With its naturalistic design, Valley challenges the distinction between urban and rural. Image © Vero Digital

With its naturalistic design, Valley challenges the distinction between urban and rural. Image © Vero Digital

Connected to the opposition of density and openness is the opposition of the urban and the rural. In an increasingly dense urban environment, access to nature has been repeatedly shown to have a beneficial psychological effect. So how do we ensure that urban dwellers can not only access natural (or at least naturalistic) environments, but find themselves immersed in them whenever possible?

MVRDV has long been interested in the combination of nature and structure, most notably in the iconic Netherlands Pavilion at the 2000 Expo in Hanover, which was envisaged as a series of stacked landscapes – including a forest on the fifth floor. This building-as-landscape approach has found its way into our collective housing projects too. In Valley, currently under construction in Amsterdam, the typology of a commercial plinth with three residential towers has been broken down into something more geological: the apartments in the towers are arranged like jagged cliff faces, complete with copious vegetation, and the roof of the seven-storey plinth can be accessed from stepped paths leading from the street, allowing the public to wander through the valley created by the apartments.

Top-Down vs Bottom-Up

.jpg) KoolKiel includes icons on the façade inspired by the creative community.

KoolKiel includes icons on the façade inspired by the creative community.

Modernism often took a patrician worldview – again, a result of the culture and politics that produced it – conceiving entirely pre-determined, ‘top-down’ housing designs that stripped any sense of autonomy or self-determination from the eventual residents. Contemporary architects understand the benefits of appropriation and self-actualisation. However, an entirely grass-roots approach to building – one with no institutional oversight whatsoever – is often problematic, with potential to create sub-standard living conditions. MVRDV’s work, therefore, often plays with the boundaries between the top-down and the bottom-up.

In the 670-home Nieuw Leyden masterplan, MVRDV designed the form of the blocks and some parameters to ensure the cohesiveness of the urban form, but gave control of each home’s architectural expression to individual designers. In Oosterwold, a new neighbourhood being completed on an area of former farmland near Almere, the masterplan is even more abstract. Homeowners can mark out a plot of any shape and are in complete control of the home they build there, but with this freedom they are bound by responsibility: homeowners are required to devote certain percentages of their land to different purposes (water, agriculture, garden space, built area, etc) in order to ensure responsible land use. They are even required to work with neighbours to develop the access roads to their properties, and provide their own water, power, and sewage. In this way, Oosterwold is a radical experiment in bottom-up planning, but we have nevertheless been careful not to submit the neighbourhood to complete anarchy.

This use of bottom-up thinking is naturally suited to masterplans, but recently we have also experimented with introducing a bottom-up system to an architectural project. The mixed-use KoolKiel proposal in Germany is essentially an accumulation of design systems, rather than fixed designs. This gives agency to the vibrant community in the neighbourhood by allowing them to give feedback on how extreme the cantilevered form of the tower should be, how intense the iconographic pattern on the façade should be, and so on. The built project will therefore be a design that, while conforming to MVRDV’s overall proposal, will be finalised by the people who have to live with the result.

References

- Berlin Voids Project Description

- Le Corbusier, Toward an Architecture. Translated by John Goodman (Santa Monica: Getty Research Institute, 2007) p.182

- Le Corbusier, Precisions. Translated by Edith Schreiber Aujame (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), p.64

- Nathalie de Vries, Miruna Dunu, & Christine Sohar, Manifesto for Architecture Speaks: The Language of MVRDV exhibition at aut. architektur und tirol, Innsbruck, Austria, 2019.

- The Why Factory, “Opening up Urbanism”, in Porocity (Rotterdam, nai010, 2018), p.210